- Home

- Dianne Wolfer

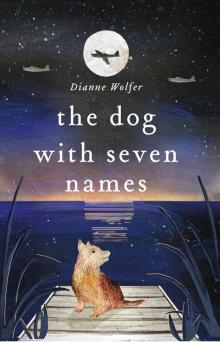

The Dog with Seven Names Page 9

The Dog with Seven Names Read online

Page 9

The next morning Doc needed to visit the Derby Leprosarium. I never knew why I couldn’t go to that place, but I sensed Doc’s sadness every time he visited. Doc said I could spend the day with Fred and Lee Wah. He let me walk some of the way to the airstrip, then he sent me back.

‘I’ll see you this evening,’ he called. ‘Look after everyone until then.’

I’d dug up an old bone and just settled down behind the bougainvillea to gnaw, when Fred rushed into the yard.

‘Matron,’ he called. ‘Come quickly. Doc’s plane has crashed.’

Fox Moth had fallen from the sky.

I ran after Fred, barking as he helped the Army doctor carry Doc into the hospital. Blood covered Doc’s arms and face.

‘I’m fine,’ Doc protested, as Matron cleaned his cuts.

‘It’s a miracle that you walked away from the wreck,’ she replied.

‘And thank goodness you weren’t on board, Flynn,’ Doc told me as Matron kept fussing. ‘You’ve already had enough adventures to last a lifetime.’

Doc wasn’t badly broken but Fox Moth was. Someone had accidentally put water in her petrol. She had to go away to be fixed.

‘How will I get to my patients?’ Doc grumbled as he limped around the hospital. ‘What if there’s an emergency?’

Fred warned me to keep out of Doc’s way.

‘He’s grumpy when he’s grounded,’ Fred said, but before long Doc found another plane.

The plane was called Swallow and I liked her better. She was smaller than Fox Moth, which was silly because real swallows are bigger than moths. Flying in Swallow was like being on the back of a bird, a bird fast enough to outfly any swooping eagle.

I was frightened the first time Doc filled Swallow’s belly tank with petrol. What if he fell from the sky again? I sniffed the petrol can until my eyes stung. Then I sniffed Swallow’s belly. It was okay. There was no water. Doc would be safe.

There were two sitting holes on Swallow’s back; one for me and one for Doc. Best of all there was no top wing above us.

‘I hope I can trust you not to wriggle,’ Doc said.

I woofed. Elsie had taught me to ‘stay’ when I was a pup, and I felt important sitting up on top in a seat of my own. Whenever Doc took me to the airstrip I danced in circles, but as soon as I was in my special place, I held my ears high and sat as still as a cornered rat.

Doc needed to fly to Mount Goldsworthy. A stockman called Old Lanky had shattered the bones in his arm. Everett said Lanky’s mates had strapped the arm as best they could, but that it needed urgent attention.

‘They’ve cleared an airstrip for you, Doc,’ he added.

It was a short flight. I leant on the inside edge of Swallow to balance and enjoy the ear-flapping breeze. When Swallow drifted through a cloud puff I gave a howl of joy. With nothing above us, it felt like we were part of the sky.

The airstrip was rough and a wind gust tossed Swallow to the side. I felt Doc tense and remembered the blood covering his body after the crash, but Doc steadied little Swallow and we landed safely. Our patient was waiting in the shade of a bloodwood tree, surrounded by his mates. My nostrils twitched. The stockmen smelt of horses, cattle and saltbush. They reminded me of Dave and Stan.

Swallow rolled to a stop and Doc lifted me out of the plane. I hopped towards the men, wagging my tail.

‘What’s happened to your dog?’ a tall man called.

‘She was caught in the cyclone,’ Doc replied. ‘Got tangled in a roll of barbed wire. What’s happened to you, Old Lanky?’

‘I’m settling in a new mare and she’s skittish.’

Lanky’s mates explained how the tall man had been crushed between his frightened horse and the cattle.

‘Ever flown in a Swallow?’ Doc asked as he checked Lanky’s injuries.

‘Never flown in nothing,’ Old Lanky muttered, ‘and I don’t want to! If you set the arm and sew up me cuts, I’ll be grateful.’

‘You need at least ten stitches –’

‘That’s okay, Doc, just do your best. The boys are nagging at me, but I don’t reckon the arm is as bad as they say.’

‘I can see bone, Lanky, and you have a gash on the back of your head. You need to be in hospital so I can treat you properly.’

The stockman grunted.

‘It’s a short flight. I’ll strap your arm and Flynn here will keep an eye on you while we’re in the air.’

Old Lanky scowled at me.

‘Strange looking nurse,’ he snapped as a sudden gust blew off his hat.

Lanky’s voice was gruff, but not mean. I felt safe with him.

Doc licked a finger and held it in the air.

‘I don’t like the way this wind is shifting,’ he murmured. ‘I don’t suppose you blokes have something I could use as a wind sock?’

One of the men grinned. ‘How about this?’

He held up a roll of the paper that humans use to wipe their tail area. A long trail unwound and floated into the air.

‘Perfect,’ Doc said. ‘If you stand on your truck and hold it high, I’ll be able to see which way the wind is blowing.’

Doc helped the injured stockman climb into Swallow’s front seat. Then he lifted me in. I curled myself around Lanky’s big feet. The smell coming from them was impressive. I took a few deep breaths of the man’s scent and licked one dusty ankle. Old Lanky growled.

As Swallow rolled down the airstrip I heard the men shout, ‘Good luck.’ Doc eased the aeroplane into the sky and Lanky gave a small moan as we took off. I nuzzled his leathery leg. A rough hand reached down to clutch my fur. Lanky’s grip tightened as Doc spun Swallow in a tight circle. I decided I should jump onto the stockman’s lap to help him feel safe. He chuckled and scratched my ear.

I closed my eyes, enjoying the cool air. Then I smelt smoke. I raised my nose and peered over the side of Swallow. While we’d been on the ground, a bushfire had started. Flames leapt across the scrubby hills. The plane pitched as Doc tried to avoid the smoke. I felt Lanky’s body tense.

‘Hold on,’ Doc shouted. ‘We’ll need to fly around this.’

Doc turned Swallow but the smoke was spreading. I peered down again. The flames frightened me. I blinked as they flickered higher. The plane bounced and Lanky’s fingers clutched my fur.

‘Sorry about the turbulence,’ Doc called from behind. ‘I’m going to fly higher. I need to get us out of this smoke. Don’t worry, we’ll climb above ten thousand feet, but only for a few minutes. If you feel breathless, take a few swigs of oxygen. There’s a cylinder beside you.’

‘What about the dog?’

‘If she starts drifting, share the oxygen or blow into her nostrils.’

‘Are you serious?’

Doc didn’t answer. He was peering at the smoke and pulling levers.

Lanky reached for the oxygen bottle with his good hand and took a couple of gulps. I pressed my nose into his belly, careful to keep clear of his injuries. Old Lanky seemed happy to have me closer. I felt his heart thudding and he didn’t push me away.

As the plane shuddered upwards, the stockman clutched his broken arm.

‘We’ll have to go higher,’ Doc called. ‘Use the oxygen. I’ll take us lower in a few minutes.’

I began feeling dizzy. Was the plane spinning?

‘Keep an eye on the dog,’ Doc yelled.

I felt Lanky’s gnarly hand grab my muzzle. Then he held a mask over my nose. The dizzy feeling stopped as Lanky and I took turns with the oxygen mask.

Doc flew over the smoke then brought Swallow closer to the ground. I panted, gulping in the sweeter air. Lanky patted my head.

‘Well, that was an adventure,’ he said. ‘Me old pearl-diving mates would give me what for, if they knew I’d been buddy-breathing with a ruddy dog.’ He chuckled, scratching my neck. ‘You’ve given me a bonzer story to tell around the camp fire, little Flynn!’

I wagged my tail, licked his rough cheek and leant against Lanky’s belly as Doc swooped a m

ob of roos on the Hedland airstrip before landing.

At the end of each day, after the sandflies settled and before the mosquitoes began whining, Doc sat in the yard reading his newspaper. Whenever he found an exciting part, Doc clicked his tongue and made strange, impatient noises.

‘Listen to this, Flynn …’ Doc said as he read on and on about air strength in something called the Pacific.

I nudged Doc’s leg, hoping for a tummy tickle as his eyes skimmed the page. Even when I didn’t understand the words, I liked listening to his voice.

‘The fighting in the Coral Sea is going well,’ Doc told me.

Fred left his chores and came to join Doc as I rolled over, showing Doc my tummy.

‘What’s the latest?’ Fred asked.

Doc flicked the newspaper. ‘They say We shall need every ounce of our present and potential strength to beat the Sons of Heaven because five months of this war have already proved that their country ranks among the great air Powers of the world. They have first-rate planes, excellent pilots, a shrewd directive and an uncommonly good sense of co-operation and tactics. They have known for years the value of air strength in the Pacific.’

‘Blind Freddy knew that,’ Fred muttered. ‘Unlike our leaders …’

Who was Blind Freddy I wondered as Doc kept reading about aircraft-carriers and seaplanes.

I gnawed a flea bite and yawned. When was someone going to pat me?

‘Their Zeroes are jolly impressive,’ Fred said. ‘Anyone who saw them strafe Broome says their manoeuvrability is first rate.’

‘They certainly gave our Wirraways a run for their money in Rabaul. I wouldn’t want to meet a Zero when I’m up in Swallow.’

‘Indeed not!’

Doc smoothed the paper and his voice became softer. ‘It is with air power that we shall beat him,’ Doc read, ‘but we won’t do it by underrating his ability or strength.’

‘Hear, hear!’ Fred called. He shook his fist at the sky. ‘What do you think, Flynn?’

I leapt up and barked.

‘I think she wants her dinner,’ Doc said.

Fred smiled. ‘Come on then.’

He led me to the kitchen and gave me a big bowl of scraps.

Human months or weeks passed (I could never work out the difference). The place called Darwin was bombed again and the submarines that everyone had worried about sneaked into Sydney Harbour, wherever that was. I remembered Elsie’s maps and wished she was here to explain how far away the places were.

Another ship sank and a lot of soldiers died. It was a Japanese ship but there were Australians called POWs on board. The ship was sunk by Americans, even though they were our friends. It didn’t make sense and trying to understand made my head spin. The ship was called Montevideo Maru and whenever Matron heard those strange-sounding words, her eyes filled with tears.

Most of Doc’s patients had been moved to Marble Bar, so we spent more time inland. Marble Bar was hotter than a camp oven and I missed Port Hedland’s breeze. The inland hospital had a matron called Joan and two nurses, Doreen and Bonnie. They were all kind, especially Bonnie, who saved me treats from her lunch.

Some of Doc’s patients refused to move inland to Marble Bar – maybe they knew about the heat – so Doc and I still flew between hospitals. Doc was busy at both places. Everyone had questions for him or wanted his advice.

‘What should we do about Mr Thomson’s eye?’

‘Can we airlift Mrs Hart before the baby arrives?’

‘We’ve almost run out of iodine.’

‘I’m worried about the rations, there’s hardly any water.’

‘Can you go to the Comet Mine to settle a mining dispute?’

Doc wasn’t just a doctor. In Marble Bar, he also visited a big stone building on the hill. Policeman Gordon brought people to Doc. Sometimes they had ropes around their hands. People told Doc stories until he made a decision. Then Mr Gordon went away and came back with another roped person.

The stone building was cool inside. While Doc was busy, I lay by the front door, keeping watch in case the mean dogs escaped their chains.

When we were at Marble Bar, I missed Lee Wah and Fred. The Marble Bar nurses were kind, but with so many patients, they were too busy to sit with me, or notice the mean dogs sniffing about.

One day a young boy came in from the desert with his family. The boy was called Arunta and his hand was huge. Arunta’s father showed Joan two holes on his skin.

‘Scorpion,’ he muttered.

‘Lucky you got to us in time,’ Joan said.

Joan said she needed to drain the poison immediately. She cut Arunta’s hand, gave him medicine and put him to bed. I smelt the boy’s fever-sweat and heard his body shaking. While the nurses cared for Arunta, his family set up camp behind the hospital. The father’s dog had golden eyes like mine. When the moon was high, we prowled through the prickly spinifex behind the hospital. Then, after Doreen and Bonnie were asleep, I led the desert dog inside the hospital. He dozed beneath Arunta’s bed until first light.

Arunta’s arm swelled all the way to his elbow. Doc told his family that he needed to transfer Arunta to the larger hospital in Port Hedland to try different medicines. There was only room for Arunta (and me) in little Swallow, but Doc promised to send radio updates for his family. I was excited to be returning to Hedland, but worried for Arunta. His arm smelt nasty.

The flight to Hedland was smooth. Arunta was a quiet boy, not quite a man but almost. He had a kind energy and being with him made me feel warm and settled. Although I smelt Arunta’s pain, and his skin was burning hot, his good hand never stopped stroking my ears. All was well. As we flew closer I poked my nose into the air. I didn’t want to miss the first smell of the ocean. And maybe Lee Wah had saved a bone for me. My tongue drooled.

When I heard the engine change I knew Doc was getting ready to land. I stood up, even though it was tricky balancing on one leg. Then I heard another sound, the drone of engines coming towards us. The aeroplanes sounded different to Fox Moth, Swallow and Electra. I nosed the air, sensing danger, but not understanding. The engine sound grew louder. My before-the-branch-fell feeling returned and I howled. Doc stared into the distance. Then his breathing quickened. He swore and suddenly Swallow dipped. I wobbled and fell against Arunta’s arm. He flinched.

‘What’s happened?’ he asked.

‘Over there.’ Doc pointed. ‘See the planes!’

Arunta held a hand above his eyes and I smelt the boy’s fear.

‘Bombers!’

‘It’s a whole ruddy squadron!’

Everett’s voice babbled a warning over the radio. Doc jerked the controls.

‘We need to get higher,’ he shouted. ‘With the sun behind us, those Jap pilots might think we’re a Spitfire.’

Arunta’s good arm clutched my chest, squeezing the breath out of me as Swallow dipped and circled. The planes growled closer. I saw clouds puff up from the runway below.

‘They’re giving the airstrip a pasting!’ cried Doc.

Swallow climbed higher. She was straining. My ears hurt.

‘Hold on!’ Doc called.

There wasn’t enough air. I panted and felt Arunta’s shoulders droop. We needed the oxygen bottle. Arunta’s head flopped onto mine and as we drifted between sleep and waking, memories flowed between us. My golden eyes saw Arunta hunting … splashing in wet-season creeks with friends … then I saw Elsie …

Doc swerved down and flew in circles, checking the sky below. At last he yelled, ‘They’ve gone.’

As Swallow flew lower we all gulped air.

‘I’m sorry, Arunta. Are you all right?’

Arunta nodded.

‘And Flynn?’

‘She’s fine.’

‘Thank goodness. Now sit tight,’ Doc said, yanking his levers, ‘we’re going down and this will be a rough landing.’

‘What if they come back?’

‘Let’s hope they don’t. I’m the only doctor. They’ll need me

.’

I felt Arunta shiver as Doc did a flyover. I looked below. Smoke covered the airstrip. Between clouds of dust I saw big holes in the runway. Was Fred down there under the smoke? And what about the hospital, had it been hit? I trembled as Doc flew over again.

‘Hold on!’ he called.

Grit prickled my eyes and Arunta coughed as Swallow lined up in front of the airstrip. We landed heavily. Swallow bounced and Arunta moaned. I turned to watch Doc steer around the ditches. He was frowning as he gripped the levers. As soon as we stopped, Doc jumped out.

‘Stay,’ Doc ordered, then he ran to help.

I wanted to follow Doc, to keep him safe, but Arunta also needed me. The boy was brave, but his skin felt dangerously hot. I nudged a water flask closer to his hand as men ran back and forth across the runway. One man told us shrapnel had hit a soldier’s head.

‘Killed him,’ the bloke said, shaking his own head. ‘The bombers dropped those daisy cutter bombs and shrapnel was flying everywhere.’

I peered around the smoky airstrip. Elsie liked flowers. I’d seen her pick daisies, but where were they and why were Japanese pilots cutting them?

Men appeared through the smoke. One of them was Doc. He told us it was too late to help the daisy-cut man, but that other people had wounds that needed stitching.

My nose was battered with smells of panic and fear. The worst was a sizzled flesh smell. It reminded me of Hendrik’s wounds and stockmen using the branding iron on cattle. Rivette came to mind, but I shook my coat. After the cyclone I’d stopped thinking about her. The only one I wanted to remember was my Elsie. I whimpered. Would I ever find her again?

Soldiers ran past Swallow. One bellowed orders. Others hurried to do what he said. A man dressed in an apron waved a spoon and shouted swear words at the sky.

‘You’ve filled my porridge with dust,’ he yelled.

I needed to pee, but sat as still as I could beside Arunta. The boy seemed dazed. He kept looking up at the sky. I couldn’t hear any more planes. We were safe for now and I licked Arunta’s leg, wishing I could tell him not to worry.

The Dog with Seven Names

The Dog with Seven Names